Servo Magazine ( January 2012 )

The History of Robot Combat: From Humble Beginnings to Multinational Sensation

By Morgan Berry View In Digital Edition

Most of the memories of my childhood are fairly typical: dance recitals, first days of school, climbing trees in the backyard, etc. Others — like a vivid memory of staring intently into a plexiglass arena while two 3 lb RC robots attacked each other — are much less common. I learned words like servo and solder, practiced tank steering through an obstacle course of orange cones in my garage, and trash talked with middle-aged nerds; I now realize none of this was a normal childhood experience.

At a young age, my brothers and I had the great fortune to become involved in the world of robot combat through my father (one of those aforementioned middle-aged nerds). The years I was involved with the sport were some of my happiest. In the haze of childhood, I had no idea that the unique niche sport I had found my way into had an equally interesting past. The small slice of the sport I had experienced was just part of a much longer history.

The Beginning

Long before the glitz and glamour of Comedy Central’s BattleBots™ brought mass appeal to the sport, robot combat had much humbler beginnings. The sport got its start in October 1989 at the ultimate breeding ground for all things nerdy: a science fiction convention. The MileHiCon — a convention running since 1969 in Denver — featured the first actual tournament promoting robotic battles called the Critter Crunch. This turbulent start is outlined in Brad Stone’s book Gearheads — a fantastic read for anyone interested in the history of robot combat. According to Stone, a small group of mechanical engineers known as the Denver Mad Scientist Club envisioned the event after viewing videos from the robotic performance art group known as the Survival Research Laboratory and learning of a competition at MIT that required homemade robots to compete in mechanical tasks like collecting ping pong balls. By coupling these influences with the already existing Critter Crawl at the MileHiCon — which a recent Wired article about the event describes as a “sort of beauty pageant for windup toys and remote-control gizmos” — the group created a robot combat event like no other.

Participants at the 1989 Critter Crunch at MileHiCon in Denver. Photo courtesy of Wired.com.

It was part eccentric spectacle, part brutal fight to the death, and all fun. This formula has carried through the sport to this day; I personally recall a bot in my robot combat league named “Cousin It” that used a cheap plastic hat as its armor which would invariably be ripped to shreds by the end of the competitions. Unlike the behemoth bots featured on BattleBots, these bots could be no bigger than one cubic foot; although, once the match started they could be expanded with appendages.

The bots could weigh no more than 20 pounds. The matches were fought on a folding table, and with spectators only a few feet away from the bots, the weapons had to be kept relatively tame. That did not, however, stop some weapons like a flamethrower or pneumatic ram from occasionally sneaking in.

Since its start in 1989, the Critter Crunch is an ongoing event at the MileHiCon that continues to appeal to eccentric, destruction-loving, creative types like those who first envisioned it.

Meanwhile ...

Eventually, word of the Critter Crunch began to spread and other conventions around the country began hosting robot combat events as well, most notably at DragonCon in Atlanta. While these non-commercial events thrived in the convention world, another man was independently developing a bigger picture view of robot combat.

Marc Thorpe was a San Francisco based animatronic designer who created special effects for the last two movies in the Star Wars trilogy for LucasFilm, which in itself is enough to inspire awe in even the most casual nerd. According to his own website http://MarcThorpe.com — while independently working on a remote control vacuum cleaner in 1992 — Thorpe looked at the device and realized its sinister potential to be transformed into a metal-crunching death machine. Using this idea and the entrepreneurial spirit he had gained from working at LucasToys, Thorpe realized the money-making potential behind a remote-controlled robot combat tournament and immediately began this new business venture.

After a few unsuccessful attempts to get the event going — which he had named Robot Wars — a feature in a 1994 issue of Wired Magazine finally gave Thorpe the monetary support he needed to put on the competition. This event was markedly different from the Critter Crunch.

1995 Robot Wars San Francisco. Courtesy of MarcThorpe.com.

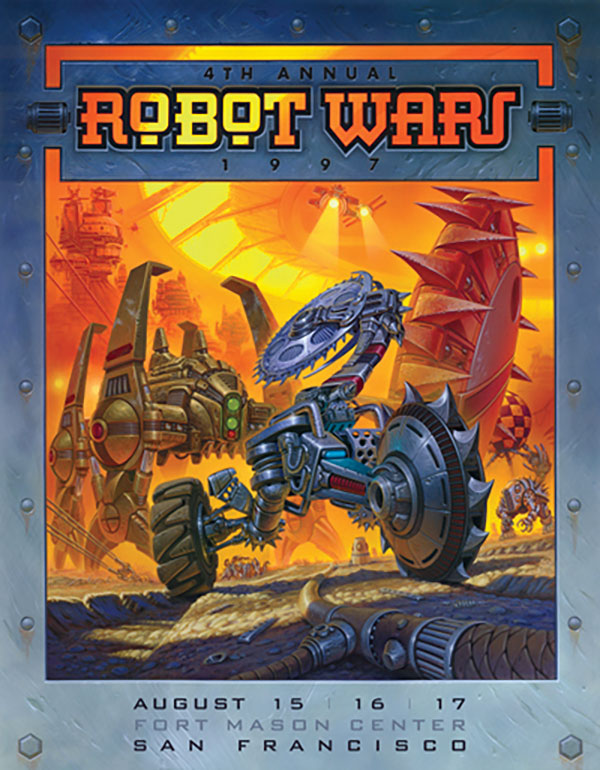

For one thing, it was independent and was not confined to the hotel ballrooms of science fiction conventions; as a result, the robots could be much larger and more dangerous. The Robot Wars brand was continually apparent through specialized posters, t-shirts, and trophies. Some notable competitors at the first event were Caleb Cheung, inventor of the wildly popular Furby toys, and Will Wright, the creator of the Sims video games. Following the massive success of the first competition, the events continued until 1997; each larger and more exciting than the last.

Courtesy of MarcThorpe.com; Copyright Marc Gabbana.

Robot Wars Expands onto Television

The business partnership between Thorpe and Profile Records began to sour as Profile Records pursued the creation of a Robot Wars television show in the U.K. Despite legal battles surrounding ownership of the brand, the series was aired in 1998 on British television. This version of Robot Wars was much different from the San Francisco competition, and completely unrecognizable from the simplicity of the Critter Crunch.

The original season involved three competitions for the robot builders. The first — called “The Gauntlet” — was an obstacle course. The second — “The Trial” — featured games like “Football” and “Tug of War.” The last challenge was “The Arena,” which required the bots to compete in the familiar combat based battles. While the arena for the Robot Wars competition in San Francisco had originated with just a two foot high plywood barrier between the audience and the bots, the television version had a complex arena with various dramatically named hazards to add another layer of difficulty to the competition. The Pit of Oblivion, the Disc of Doom, and the Floor Flipper were just a few of the hazards the bots would face.

Another notable difference from previous competitions was the addition of “House Bots” which were not confined to the weight or weapon constrictions of the competitors, and could attack the competing bots if they ventured into certain zones of the arena. The show proved to be a wild success, spanning seven seasons and sparking multiple spin-off shows and a line of “House Bot” children’s toys.

Legal Turbulence Sparks Greatness

As an event timeline from RobotCombat.com outlines, as the British television show began to takeoff, legal battles hindered the growth of robot combat in the United States. Back in San Francisco, those involved in the original Robot Wars competition were preparing for Robot Wars ’98 when Profile Records issued a court order barring Thorpe from holding the event. Profile also attempted to shut down the Robot Wars Internet forum the group had created.

To prevent the builder’s hard work from going to waste, an invitation only, spectator-less event called Robotica was organized, only to once again be barred from taking place by Profile. Eventually, Thorpe would also lose his ownership of Robot Wars, and when veteran robot builders Trey Roski and Greg Munson attempted to organize an entirely new competition — the now famous BattleBots — they were also sued by Profile Records.

The future of robot combat was beginning to look bleak when, finally, the sport’s luck began to change; the court had ruled in favor of BattleBots. With a break in the legal battles finally allowing competitions in San Francisco again, the golden age of robot combat was about to begin.

Coming up in the next installment of this series will be The History of Robot Combat: BattleBots Brings Mass Appeal to the Sport. SV

Article Comments