Servo Magazine ( March 2012 )

The History of Robot Combat: Life After BattleBots

By Morgan Berry View In Digital Edition

After the cancellation of Comedy Central’s BattleBots in late 2002, many in the building world felt lost. BattleBots had grown the sport of robot combat from an obscure niche activity to a national television event. Robot combat and BattleBots had become household terms. Suddenly, the backbone of the sport was gone, and that left many with questions as to the future of the sport. Would robot combat continue to survive without the support of those national television audiences?

The builders did not wait long to mourn the ending of BattleBots. In fall 2002, Ken Gentry began planning a competition in Orlando, FL. Many hoped that this event — Robocide — would be the next “big thing” in the wake of the ending of the BattleBots television program.

This first major event since BattleBots — quite appropriately held on New Year’s Day in 2003 — attracted many well-known bots including Son of Wyachi and Phrizbee-Ultimate. To gain a perspective on this event, I sat down with Combat Zone editor at SERVO, Kevin Berry, to talk about his experience. Because this was his first ever competition, he was able to gain the perspective of a new “outsider” looking in on the veterans of the sport.

Kevin built a 55 pound bot, Chupacabra, which he describes as both “lame” and “pathetic,” and unfortunately, was scheduled for the very first fight in the competition against veteran Dick Stuplich’s 2EZ. His first experience in the box lasted approximately 20 seconds, ending with 2EZ turning the poor Chupacabra into — in Kevin’s words — “coleslaw.”

This harsh induction into the world of robot combat taught Kevin something that surprised him: Watching your own bot get destroyed is just — or at least almost — as fun as destroying someone else’s. Really, although winning is of course ideal, robot combat is just all around fun to be a part of. He finally understood those moments he had witnessed on BattleBots where a driver cheered on his competitor as his own robot was torn apart. Of course, that spirit would be nowhere to be found without the good sportsmanship of the competitors which Kevin says was the other lesson he learned that day.

As he met the more famous faces of robot combat, every single person was “gracious, informative, and approachable.” Everyone at Robocide did their best to welcome Kevin into the sport which he would, in turn, eventually do for the other “newbies” he met. The things he experienced at Robocide were very indicative of the spirit and manners of robot combat.

All in all, the event was a great success and set the tone for 2003 to become a very active and positive year in robot combat. If you would like to see videos from this event, Robert Woodhead has a great catalog of the fights at Robocide on his website at www.madoverlord.com/robots/robocide.t.

Robocide was among many regional events held in 2003. As Terry Ewert from Team Wyachi puts it, “It seemed like we were on the road every month, from Harrisburg and Pittsburg, PA, to Orlando and Ormond Beach, FL, to Minnesota and Saskatoon in Canada, to Los Angeles.” Along with this myriad of smaller events, there was also an effort to create a national organization.

Battle Beach was held in Daytona Beach, FL on March 4th, 2003.

Brian Nave, the event host, intended the event to correspond to Bike Week — a 10 day festival for motorcycle enthusiasts. This competition featured a unique arena design. Since it was made to fit on a curved stage, the arena was hexagonal, long, and narrow, rather than being fairly square like most other arenas. This made for some interesting fights, as the speedier bots had plenty of room to get up to full speed in the long arena. Terry Ewert went so far as to say the best match he has ever seen took place at Battle Beach. This fight — Toro versus The Judge — went the full three minutes with no knock-outs and was almost non-stop action. Both 340 lb bots were flung into the air at times during the fight.

The competition was very well attended; 106 total fights were held. Nora Judd, a competitor at Battle Beach, repeated Kevin Berry’s message about the camaraderie at all the events in this time period. Brian Nave was short on helpers (she explained to me), so many people stepped in to help run the event. She ran the pit area and her husband, Steve Judd, was in charge of organizing judging. Another Steve — Steve Buescher — set up the schedules while yet another — Steve Brown — helped out, as well. Battle Beach was held annually through 2006, with subsequent battles featuring large insect battles (for more information, stay tuned for next month’s article on “The Rise of the Insects”).

Battle Beach served as the Southeastern qualifier for a larger, national competition. The national competition — known as the Triangle Series Nationals — was sponsored by the Robot Fighting League. Finalists from Battle Beach, Mechwars (the Northern qualifier) and Steel Conflict (the Western qualifier) competed in Minneapolis, MN on September 19, 2003. Nora Judd (who was the first female driver to make it to Nationals) again recalled how the tireless efforts of numerous builders came together to create the large event. Although she admits it was disorganized — as so many robot combat events are — everyone pitched in to make the Triangle Series Nationals a success.

In addition to the events held during 2003, there was also growth on the administrative side of the sport. The Robot Fighting League was formed in November 2002 by a group of builders who wanted to standardize and expand robot combat. Steve Judd, Fuzzy Mauldin, Bob Pitzer, and Steve Brown were among those who attended a highly secret meeting at an event in Las Vegas. It was so secretive, in fact, that even Nora Judd (wife of RFL founding member Steve Judd and an active robot combat participant) was kept in the dark about it. They met out of necessity; as Nora explains, “BattleBots had been cancelled and everyone was having so much fun. We wanted to keep playing! We didn’t know exactly where we were going, but we knew that we wanted to continue.”

What formed out of that secretive first meeting was a loose confederation between independent events held all over the world. RFL sanctioned events were subject to a set of rules and safety standards. These new standards arose to fix the issues that some builders saw with the BattleBots regulations (which couldn’t legally be used outside of a BattleBots sanctioned event, anyway). Because of the high number of RFL sanctioned events (there were over 2,000 matches at RFL events in 2003 alone), builders could be assured consistency in the competitions they attended. The RFL also employed a system where new event organizers were sponsored by a more experienced organizer to ensure safe and successful matches.

In the year immediately following the ending of the BattleBots television show, there was a definite change in robot combat; 2003 was characterized by a return to the grassroots, homegrown spirit that originally sparked the creation of robot combat. An inclusive, tight-knit group of builders were working to ensure that the sport was not going to fade away. In fact, in many ways, it was better than ever.

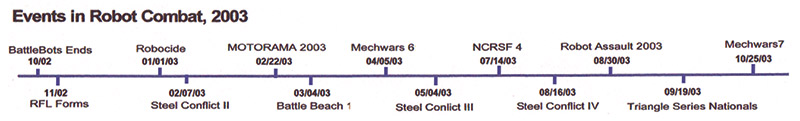

For more information, check out the timeline of some of the major events in robot combat in 2003, or go to Botrank.com or Buildersdb.com. Special thanks to Kevin Berry, Terry Ewert, and Nora Judd for the wealth of information they were able to provide about this period in robot combat.

Next month in our series will be The Rise of the Insect: Antweight and Beetleweight Competitions. SV

Note: Unfortunately, the builders of this time period seem to have done a spotty job at recording the events of the day. As a result, I had a difficult time piecing this article together. I did my best to dig up all the information I could, but if any readers notice anything I've left out or misconstrued, please post here in the comments to set the record straight.

Article Comments