Servo Magazine ( July 2012 )

The History of Robot Combat: RoboGames

By Morgan Berry View In Digital Edition

Note from the editor: Combat Zone declared 2012 “History Year,” and commissioned a young writer to produce an article series attempting to pick up where Brad Stone’s excellent book, “Gearheads” left off. This month, Morgan continues digging into the very raggedly documented history of our sport with this piece on RoboGames. In case you’ve missed other editions, she covered The Early Years in January, BattleBots in February, the post BattleBots transition in March, a comprehensive investigation into The Rise of the Ants in April, and Beetles last month.

After the ending of BattleBots in 2003, a void was left in the world of robot combat competitions. A myriad of small competitions emerged to partially fill this void, but even with this flourishing of activity across the country, there was a noticeable absence caused by BattleBot’s end. While there were some national events, nothing as large or encompassing as BattleBots was quick to take root. But then, that all changed.

While local competitions are still active across the country, they have been majorly scaled down and are less active than they once were in the early 2000s. In many ways, the robot combat portion of the festivities at RoboGames is the current answer to BattleBots. The largest robot combat event in the United States — and even the world — RoboGames has shifted robot combat back from a small grassroots movement to a centralized sport, much like it was during the BattleBots days.

The Beginning#Bot Cam Video

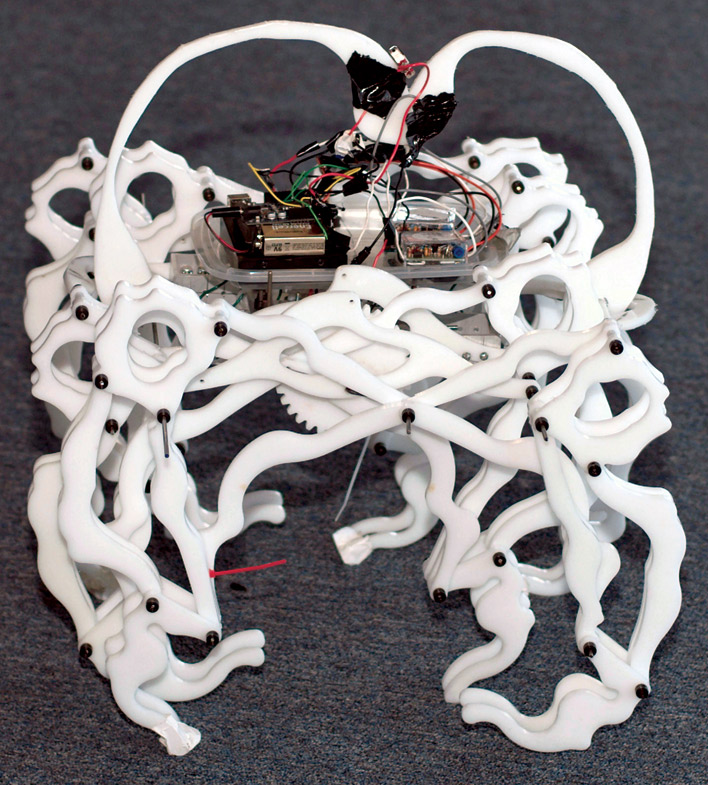

It was not David Calkins’ — the founder of RoboGames — intention to create a successor to BattleBots. Calkins created RoboGames in order to foster collaboration between the different sectors of robotics enthusiasts. While participating in various kinds of robotics events, Calkins realized that roboticists tended to become extremely specialized in their particular area while ignoring all other areas. Combat enthusiasts stay in their circle, while the makers of Sumo bots (autonomous robots that use sensors to try and force the competitor out of a circular arena) also kept to themselves. The android enthusiasts, the robotic soccer programmers, and the makers of art bots also largely collaborated only with other builders from their own discipline.

PHOTO 1.

Calkins saw this as a problem because although every one of those hobbies is undisputably cool, they really only rely on a few skill sets to compete. Most combat robots do not use a lot of computer programming or sensor technology to compete, while the other disciplines utilize completely different technologies during competition. Calkins began to realize that collaboration and “cross-pollination” across these different areas could make all of these already awesome sports even better. He could think of no better way to accomplish this than to create an event that brought all of these sports under one roof. If Sumo, soccer, and combat events were physically in the same place, the participants in these events could not help but collaborate with each other. In 2004, Calkins brought this vision to life and hosted the first RoboGames competition.

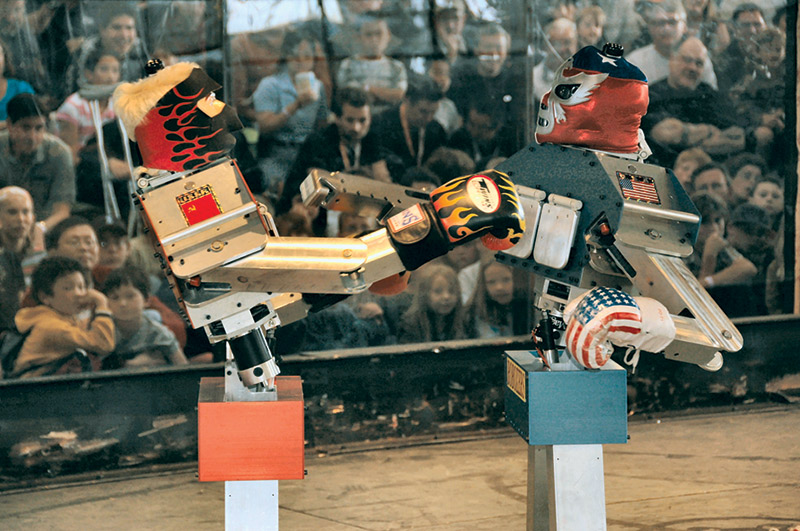

PHOTO 2.

What’s in a Name?

After developing the idea, Calkins named his competition RobOlympics. Bringing together all of these different competitions in robotic sports and the inclusion of competitors from all over the world very much mimicked the human Olympic Games. Calkins even decided to hand out gold, silver, and bronze medals to the winning robot designers. However, two weeks before the second annual competition, RobOlympics was abruptly renamed RoboGames.

Why the sudden change? As has often been the case in the world of robot combat, legal disputes were to blame. The United States Olympic Committee (USOC) wasn’t too happy about Calkins’ choice. The USOC has a long history of strictly enforcing the Olympic trademark, going after any event using the word in their title. Despite receiving international news coverage, the first competition in 2004 went off without a hitch. Just weeks before the 2005 event, however, the USOC sent a cease-and-desist letter to the Robotics Society of America, the event’s host. San Francisco State University — afraid of legal repercussions from the USOC — threatened to cancel the event if the name was not changed. Although he was reluctant to give in, Calkins changed the name, and the competition has been known as RoboGames ever since.

The Early RoboGames Events

The initial RobOlympics competition in March 2004 saw some famous faces from the robot combat world. Trey Roski, BattleBots founder, served as a judge for the combat events. Popular 316 lb The Judge — a former BattleBot driven by father and son team Scott and Jascha Little — took home the first gold medal in heaviest weight class.

Tombstone — a successful superheavyweight designed by Ray Billings — debuted at the competition and placed second in the category. The first match Tombstone fought at the event was against a wedge called Blue Max, driven by (as best as my research can uncover) Adrian “Bunny” Dorsey. Between the blade on Tombstone and the speed of Blue Max, the safety coordinator Steve Judd and the designer of the arena Steve Brown were worried that the arena wouldn’t stand up to the power of these two bots. Parts flew across the arena, hitting the Lexan and giving the spectators and the judges quite a scare.

PHOTO 3.

In the end, Tombstone defeated Blue Max, and went on to take home the silver medal. Billings won another gold medal in the junior league competition with his bot The Mortician, which still competes in RoboGames to this day — winning a silver medal in this year’s event. When asked what stood out to him about the first event, Billings said, “That first event was a blast, and you could tell it was the start of something big, something special. I’ve been to every one of them since the beginning, and I still get the feeling that it is something special every time I go.”

RoboGames Today (2012)

Since the first years of RoboGames — where Calkins financed most of the competition himself — the event has grown considerably. According to the RoboGames website, the robot combat events draw tens of thousands of spectators. While many of the spectators are initially attracted to the event because of the combat portion, they find themselves equally enthralled with the other sports, as well. In this way, RoboGames is expanding common knowledge of robotics competitions.

Even the competitors find themselves drawn to the sports outside of their area of expertise, as Professor Marco Meggiolaro, professor at the Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil and one of the top robot combat builders in the world, explained. Professor Meggiolaro has taken a team of students to compete in RoboGames every year since 2006. Even though he was too busy managing his team of 10 combat robots to watch them live, he watched videotapes of Sumo and hockey events — his favorite non-combat events — recorded for him by his students.

PHOTO 4.

As for the cross-pollination that RoboGames tries to encourage, Meggiolaro explains that in addition to learning about different components from other competitors — such as the faster sensors used in Sumo — at RoboGames, he has also learned first-hand that “combat is the ultimate test of any component.” “For instance, we were able to blow three 200A rated (continuous-current) very high-end brushless ESCs (electronic speed controllers), which — in theory — were blow-proof, even using all the manufacturer’s settings and protections specific to our “application,” given over the phone by the owner himself. If you want to test the limit of anything, try it in our bots; we will break it or blow it!” Meggiolaro says.

Meggiolaro’s RioBotz team fared well at RoboGames this year, winning medals in Sumo, combat, and solar-powered bots. Although a somewhat experienced team caused some “rookie mistakes [that] cost a few matches for Touro Light, Maloney, Touro, and even Touro Maximus this year,” RioBotz still had triumphant moments. In a rematch of a 2011 loss to Biolho — a multibot from Team Kimau ánisso — Touro Lite had a big win, making for one of Meggiolaro’s favorite moments from RoboGames. “Touro Light not only opened up both robots, popping out a few batteries from them, but also shot both of them across the entire arena to the dead zone, like a goal kick in a soccer match. It was a fun fight. The entire chassis of both Biolhos were given to us as trophies.” Meggiolaro said.

Wendy and Matt Maxham — long time competitors at RoboGames — witnessed an explosion of popular interest in the event after the Science Channel featured the combat robots from the 2011 RoboGames. “This year’s RoboGames was quite different from previous years outside the arena. Sewer Snake is usually a crowd favorite with some people stopping by to ask questions about the bot. This year, however, the sheer number of people squealing “OMG — it’s Sewer Snake!” was incredible. We had a steady stream of people (builders and audience members) at our pits area asking questions and for autographs. We signed trading cards, shirts, Antweight robots, even scraps of paper. By the end of Friday (the first day of competition), Matt and I were both hoarse from talking so much. Why were so many more people into Sewer Snake than in previous years? “Killer Robots: RoboGames 2011,” the Science Channel show from last year’s competition. Winning a televised event really brought out the fans,” Wendy told SERVO. Another change for Wendy and Matt at Team PlumbCrazy for this year’s event was the inclusion of a camera on Sewer Snake which provided an awesome close-up view of the fights (see video). More videos can be found on YouTube by searching “Sewer Snake Robot.”

VIDEO 1.

The goal of RoboGames is to bring builders of different types of bots together, and it appears to be succeeding at this. From all over the world, some of the best combat builders come to compete in a first class competition in all weight brackets. They congregate, collaborate, and walk away with new ideas for their bots. By serving as a central hub for robot combat today, RoboGames is not only keeping the sport alive, but causing it to thrive by fostering creativity and ingenuity among the builders. SV

Article Comments