Dr. Earnst Stuhlinger - Rocket Pioneer and Space Visionary

By Annie Smith View In Digital Edition

My granddaughter recently represented her high school in Mountain View, CA at the FIRST competition in Houston, TX. This event generated my interest in writing about robots, starting with a historical profile of Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger.

Years ago, as NASA celebrated their 50th anniversary and prepared to go to the moon again and perhaps on to Mars through their Constellation program, one of their rocket pioneers, Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger died on May 25, 2008. Dr. Stuhlinger envisioned a path to Mars and the means to get there over 40 years ago. Ironically, this renowned physicist died on the day NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander arrived on the Red Planet to explore for the possibility of life.

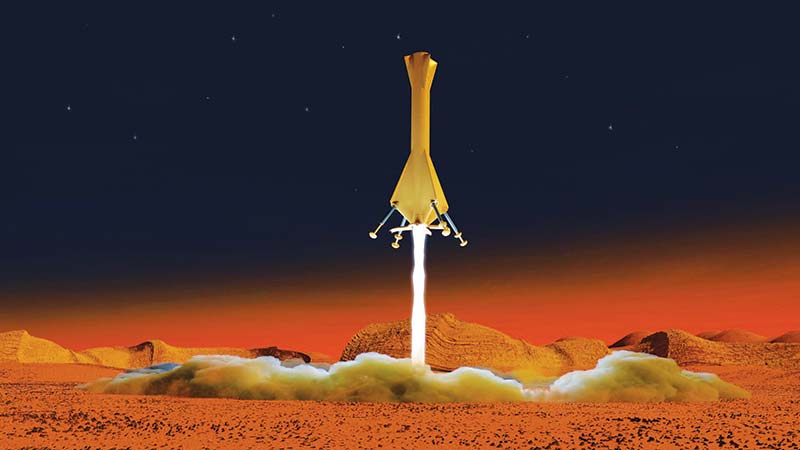

Dr. Stuhlinger thought an advanced ion propulsion-based spacecraft would be the transportation needed to get to Mars. He presented a paper, “Possibilities of Electric Space Propulsion,” in 1955 at the International Astronautics Congress in Vienna. He explained that the lighter electric propulsion system would make planetary missions more feasible.

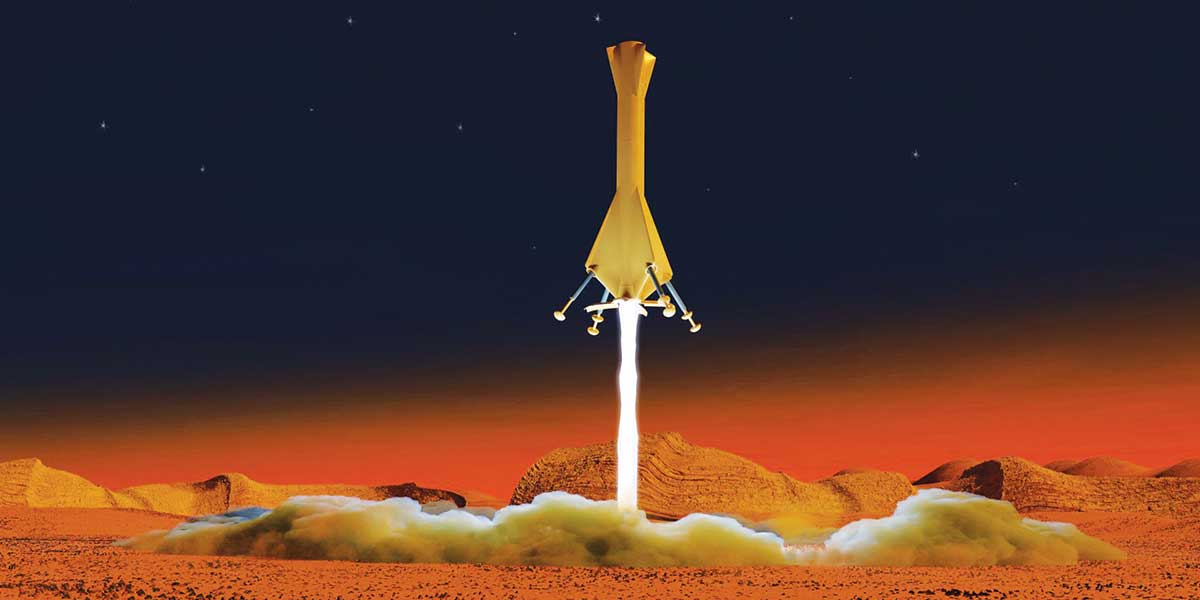

Final version of Stuhlinger’s Mars ion rocket.

McGraw-Hill published his book, Ion Propulsion for Space Flights, in 1964. NASA transferred Dr. Stuhlinger’s initial work on electric propulsion to Lewis (now Glenn) Research Center in Cleveland, OH. Stuhlinger, however, continued to help Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, AL, develop the Saturn rockets to power the Apollo program (1).

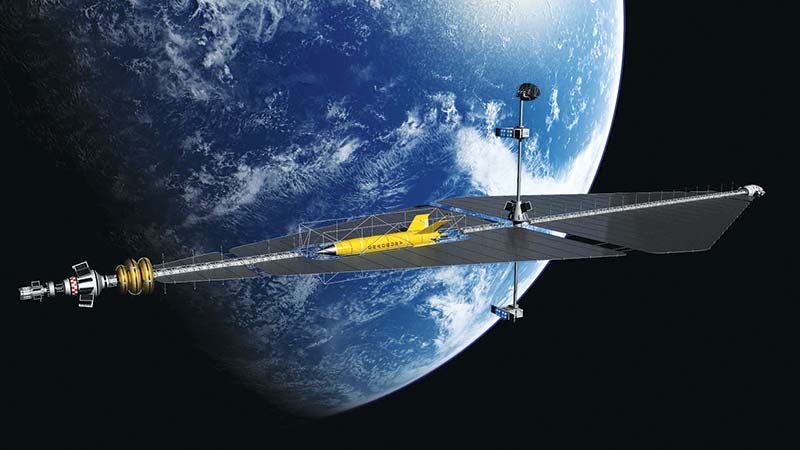

The Deep Space 1 spacecraft, launched by NASA in 1998, used ion propulsion for its missions

Deep Space 1 spacecraft.

Other Russian and American missions have also used this technology to conserve fuel and extend the life of spacecraft (2, 3).

Dr. Stuhlinger was born in Niederrimbach, a small farming village in southern Germany, on December 19, 1913. He received a Ph.D. in physics with a dissertation on cosmic rays from the University of Tüebinzen in 1936. He continued research on cosmic rays and nuclear physics as an Assistant Professor at the Berlin Institute of Technology.

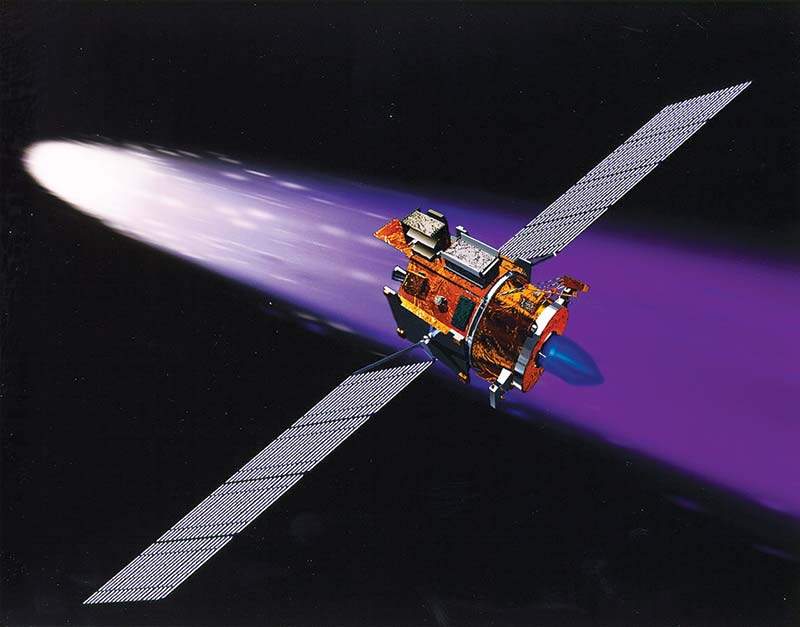

Ernst Stuhlinger’s 1954 concept, ‘Sun Ship to Mars’ combined solar power and cesium ion drives; Frank Tinsley art.

Later, he was drafted into the German army and served for one and one-half years as an infantry soldier on the Russian front. He was one of the few in his unit to survive the Battle of Stalingrad.

He was then assigned to evaluate data acquired in test flights of the V-2 rockets. He worked on the development of rocket guidance and control systems with Dr. Werhner von Braun at the German rocket facility at Peenemuende on the Baltic coast (4).

Dr. Stuhlinger is remembered not only for his scientific expertise, but also for his humanity. Dr. Lutz Gorgens, the German Consul General in Atlanta, attended the funeral and noted Dr. Stuhlinger “… embodied the best German virtues as a scientist and family man. He was a true icon of German and American friendship (5).

Stuhlinger helped von Braun build the Rocket City Observatory, now the von Braun Astronomical Observatory and Planetarium, on the top of Monte Sano. This effort enabled Huntsville children to have the opportunity to investigate space.

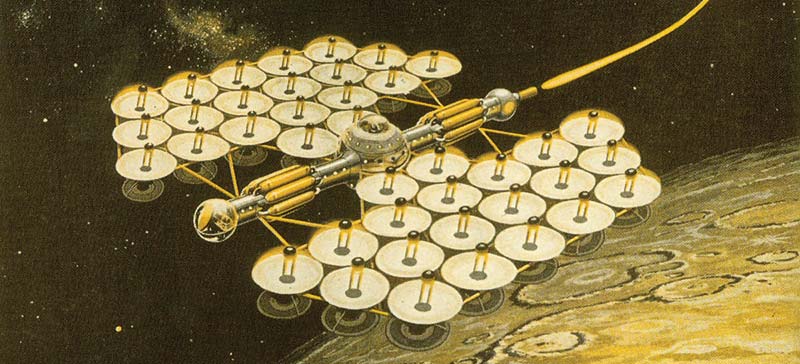

Ernst Stuhlinger’s nuclear-ion umbrella ship; art by Owen Richards.

A nun in Zambia, who worked with starving children, questioned him about the money spent on space instead of feeding the world’s hungry. He responded by writing a detailed letter to her explaining how space exploration would benefit life on Earth (6).

In February 2007, during NASA’s 50th Anniversary celebration, the daughter of Russian scientist Sergei Korolev (who developed the Sputnik satellite) spoke at the event. She also visited Dr. Stuhlinger who was hospitalized at the time.

Stuhlinger’s brother had been killed at the Russian front during WWII, and Stuhlinger himself had been wounded by a Sergei Korolev designed missile. Despite that, he gave the Russian scientist’s daughter some money to put flowers on her father’s grave in Moscow (7).

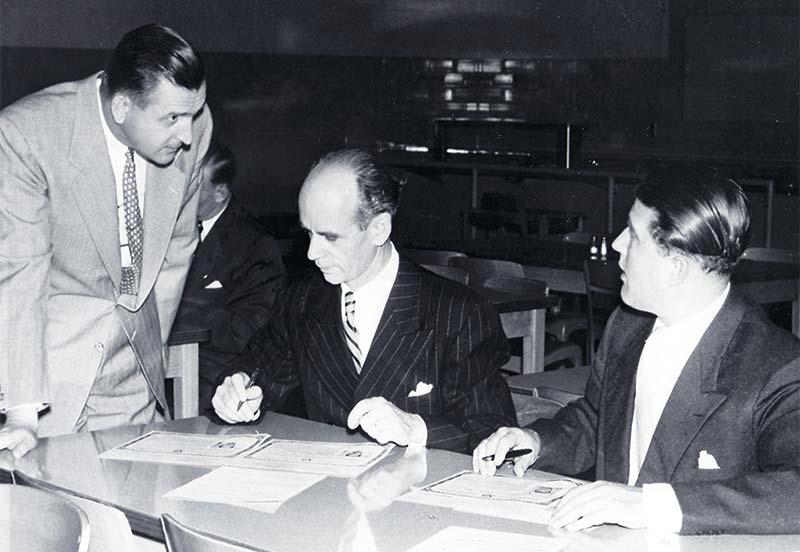

This photo shows (from left to right) Martin Schilling, Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger, and Dr. Von Braun signing certificates of citizenship in April 1955.

Dr. Stuhlinger was one of a group of German scientists brought to the United States by the US Army after World War II for Operation Paper Clip. They were to continue their rocket development for America. The team, under the leadership of Dr. Wernher von Braun, did rocket research first at Fort Bliss, TX.

These scientists moved to Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, AL, in 1950. Dr. Stuhlinger became a naturalized American citizen in 1955. This group formed the engineering foundation of the space program.

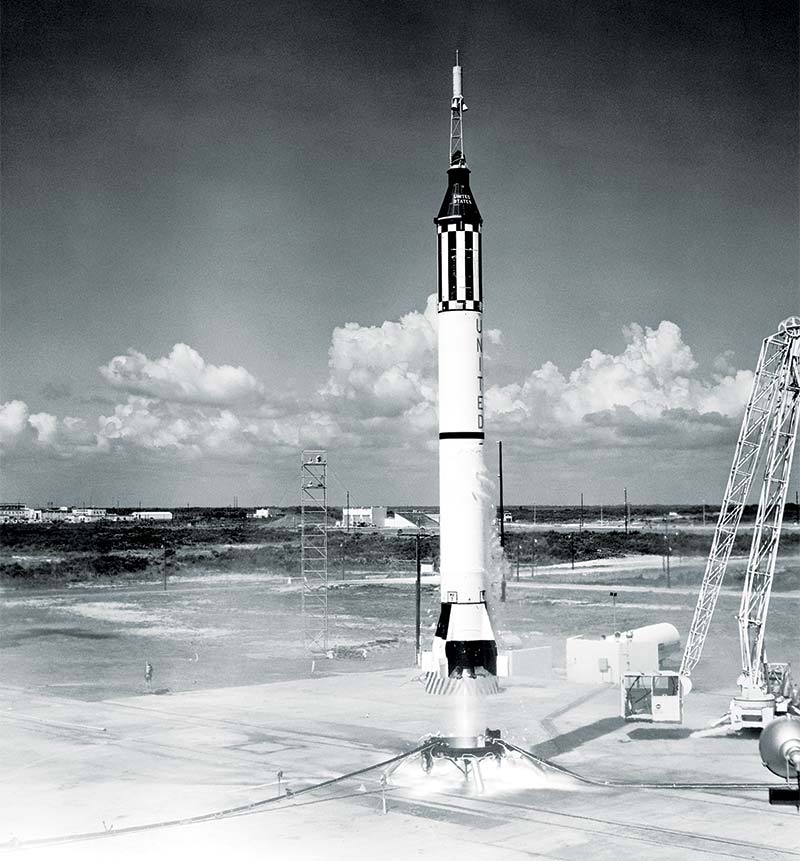

Their work led to the development of a modified Redstone rocket that launched the Freedom 7 spacecraft and sent America’s first astronaut, Alan B. Shepherd, into space in 1961.

Freedom 7 spacecraft.

After NASA was established in 1958, the team became part of this organization at the Marshall Space Flight Center. They helped put American astronauts on the moon in 1969.

Dr. Stuhlinger’s expertise in guidance and navigation instruments for space flight was instrumental in the first and subsequent space flights. He developed in his home garage the timing device for the second stage firing of the rocket. It had to be exact to put the satellite in orbit.

He pressed a button at Cape Canaveral, FL, on January 31, 1958, for the second stage successful firing. The Jupiter-C rocket launched America’s first satellite, Explorer I, into orbit (8).

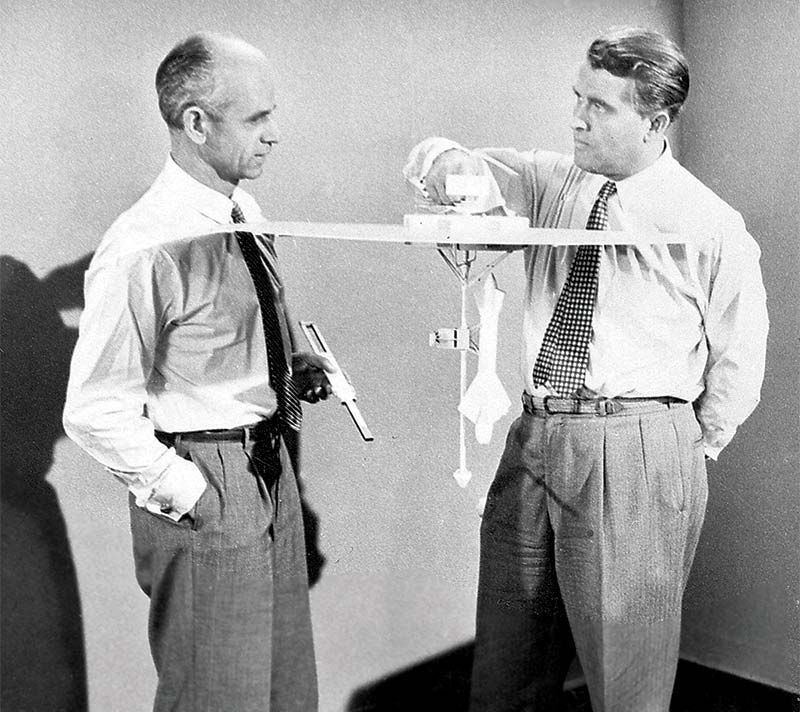

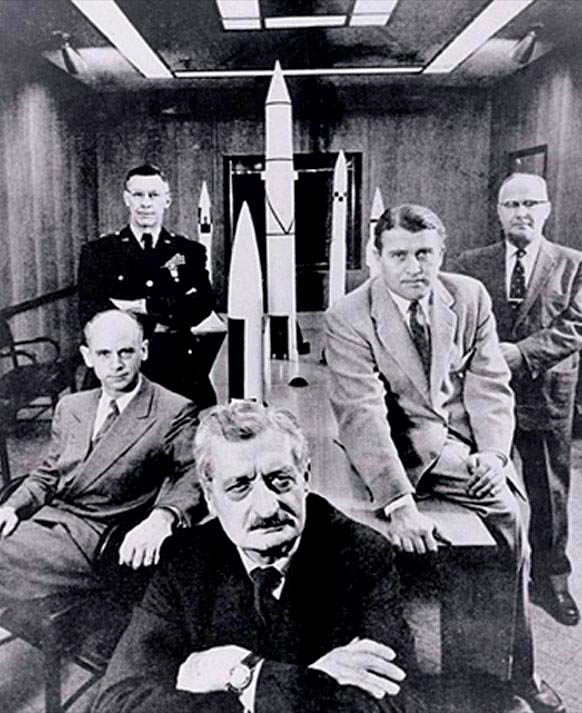

This photograph shows William H. Pickering, James Van Allen (center), and Wernher Von Braun holding up a model of Explorer I.

As director of the Space Science Laboratory, Dr. Stuhlinger also worked on Skylab (the first American Space Station), three High Energy Astronomical Observatories, lunar exploration projects, and the Hubble Space Telescope.

He convinced his colleague, space scientist James van Allen, to put a Geiger counter on board Explorer I. Stuhlinger had worked with Dr. Hans Geiger in Germany on the development of the Geiger counter to measure radiation. This suggestion led to the discovery of radiation belts around Earth (9).

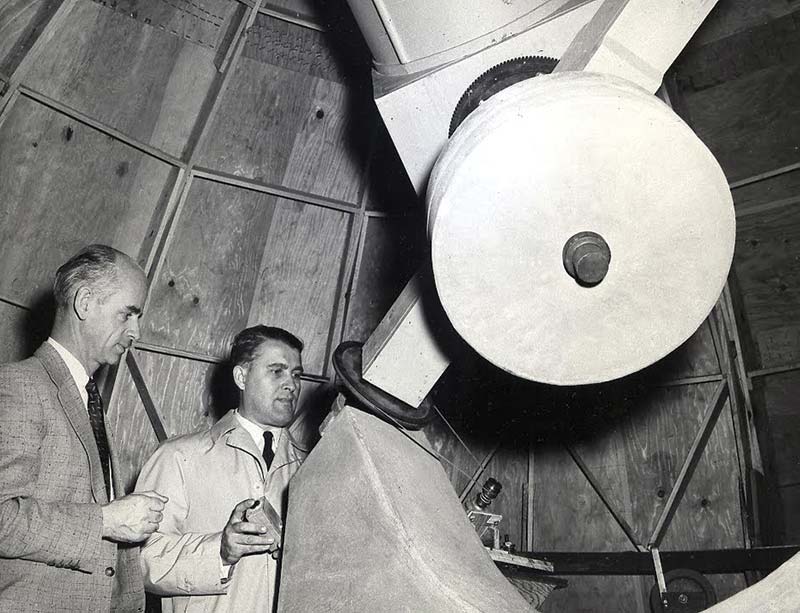

Dr. Von Braun, right, is shown in this photograph taken in the 1950s with Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger. The two are shown discussing concepts for a Walt Disney television special on the exploration of space.

Dr. Stuhlinger and Frederick I. Ordway III, a historian on the German participation team in the American space program, collaborated on a biography of Dr. Werhner von Braun who died in 1977. Their book, Werhner von Braun: Crusader for Space, was published in 1993 (10).

Five rocketry pioneers pose with scale models of the missiles they created in the 1950s. From left to right are Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger, Major General Holger Toftoy, Professor Herman Oberth, Dr. Wernher von Braun and Dr. Robert Lusser.

Dr. Stuhlinger retired in 1976 after more than 30 years of government service. After his retirement, he taught astrophysics and space science at the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH). He also became a senior research scientist at UAH and in industry. His reputation as an innovator in space technology is legendary (8).

When Dr. Stuhlinger’s neighbor, Ralph Petroff in Huntsville, AL, was asked for a comment after the scientist’s death, the neighbor summed up Dr. Stuhlinger’s life succinctly.

Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger and Dr. Wernher von Braun at the RCAA Observatory in 1956.

“He is equal part Albert Einstein and Mahatma Gandhi — a brilliant scientist with the soul of a saint” (11). SV

Article Comments