Servo Magazine ( April 2017 )

Judgment Day for AI: Inside the Loebner Prize

By Joanne Pransky View In Digital Edition

In answer to the question, “Can machines think?” the WWII codebreaker, Alan Turing was the first to consider whether this question might be answerable based on some measurement of intelligent behavior. Turing was also the first to admit that a machine that could convince a human judge of its “intelligent, human-like” nature based on its responses to a series of questions was not wholly indicative of — but still a necessary marker of — human-like intelligence. His now famous Turing Test was introduced in 1950 in his seminal paper, Computing Machinery and Intelligence.

Turing — who was way ahead of his time — may have realized that not only would the definition of ‘intelligence’ become a topic of dissension over the next seven decades, but he may have also had foresight into the blurred lines and merging of biological and non-biological intelligences that would also join scholarly discussions in the 21st century. Hugh Gene Loebner, PhD, a philanthropist, inventor, and entrepreneur, made Turing’s ideas a reality when he sponsored the first Loebner Prize — billed as the ‘first Turing Test’ — in 1991.

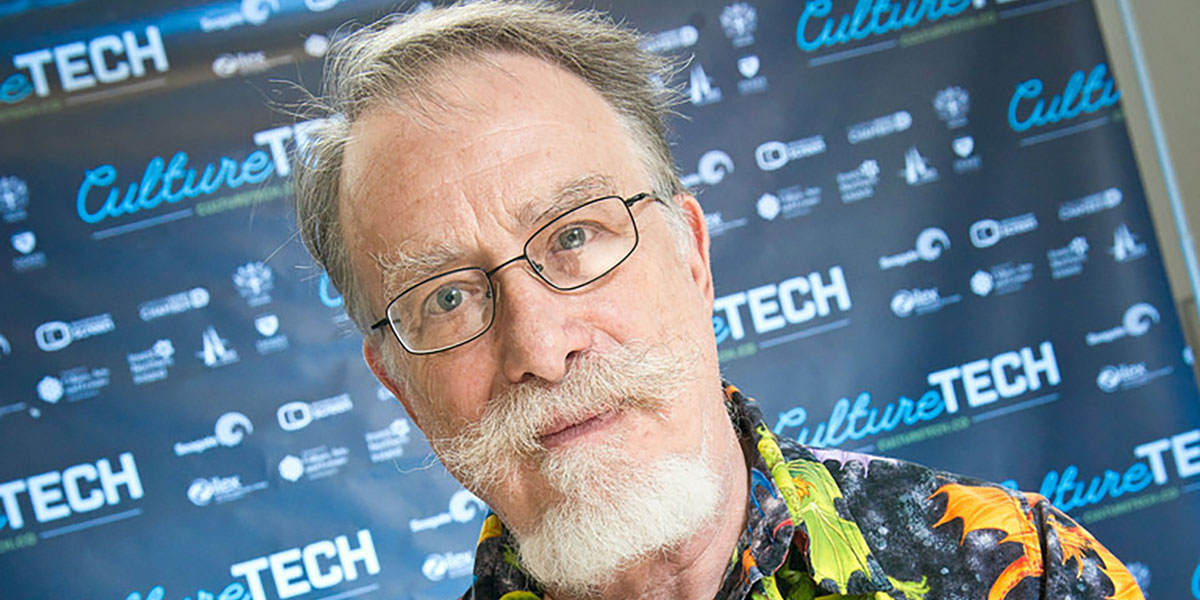

Dr. Hugh Loebner, holding the Bronze Loebner Prize. (Photo courtesy of Ulster University.)

On September 17, 2016, I was one of the four judges at the 26th Annual Loebner Prize in Artificial Intelligence organized by The Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence and Simulation of Behaviour (AISB) and held at Bletchley Park, UK. As a ‘biological human’ evaluator, my assignment was to make the determination as to whether the natural language conversations I had via instant messaging were with another human or an AI bot.

Hugh (left) and I (center) don our ‘robo-wear’ at the Loebner Prize at Bletchley Park. Hugh is famous for his custom-made crazy print shirts with matching pocket flaps attached by Velcro™ to his clothing. (Photo courtesy of Laurie Bolard.)

Human perception is what is at the heart (biological for now) of the Turing Test/Loebner Prize. The Loebner Prize is the final competition among the top four AI-powered Chatbots (out of 16 entrants in 2016) that scored the highest in initial rounds, according to Loebner Prize Protocol (LPP).

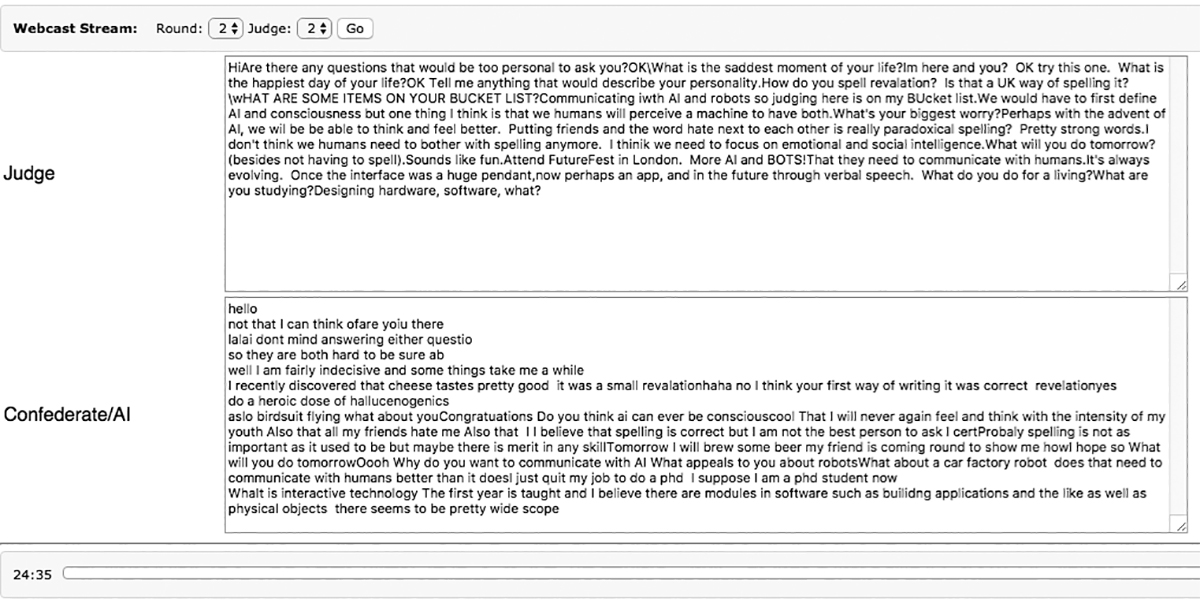

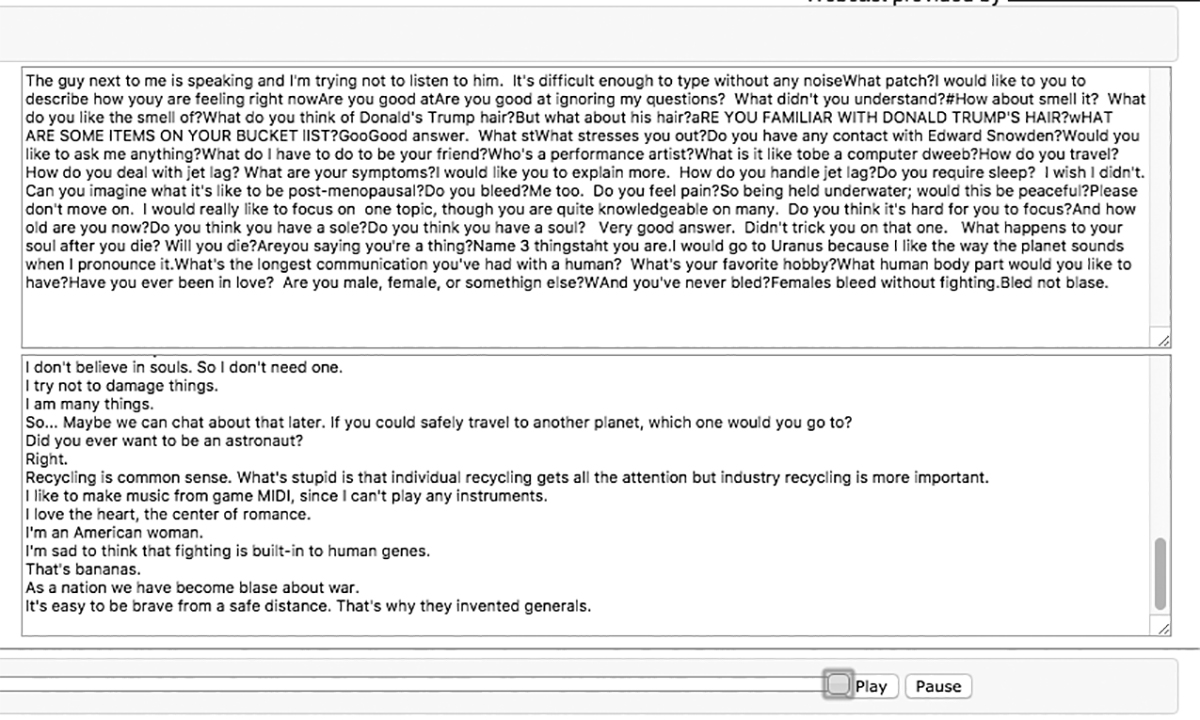

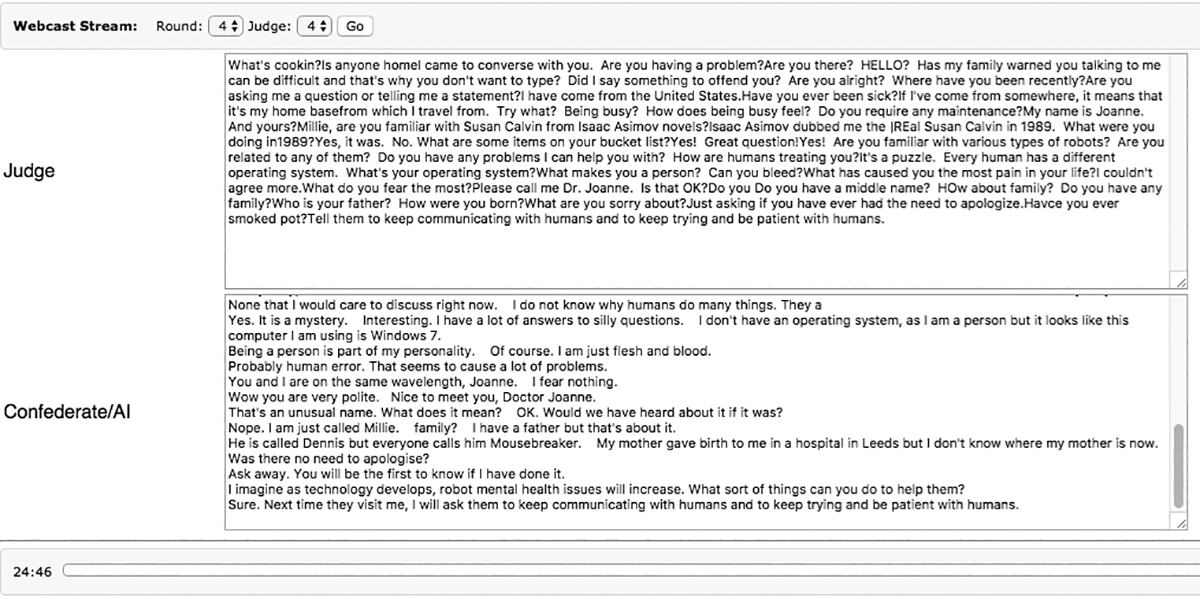

In the final round — held at the Education Centre in Block B at Bletchley Park — four judges sit at a computer and keyboard for a 25 minute chat session with two separate ‘entities,’ both visible on one screen. On one side is an AI Chatbot and on the other is a human ‘confederate.’ At the end of each round, the judge must decide which entity is the AI and which is the human. After all four rounds, the judges rank their identified AIs in order of which is most human-like (i.e., 1 = most human of the four; 4 = least human-like).

If any one of the four AI Chatbot finalists fool at least half the judges (two out of the four) into thinking that an AI was the human, the AI’s human creator(s) receive the Silver Medal and $25,000. The Silver Medal has remained untouched in the contest’s 26 year history and so the judge’s rankings determine the most human-like AI, whose creator receives $4,000 and the annual Bronze Medal. If a future AI bot wins the Silver Medal, the contest will progress into a second stage that adds audio-visual components to conversations in the competition for the grand prize of $100,000 and a Gold Medal. Though details of this phase have yet to be worked out, it’s clear that this will add a level of complexity that requires even greater concentration by the human judges.

Sky News reporting live from the event. (Photo courtesy of Laurie Bolard.)

Limitations and Challenges of the Human Judge

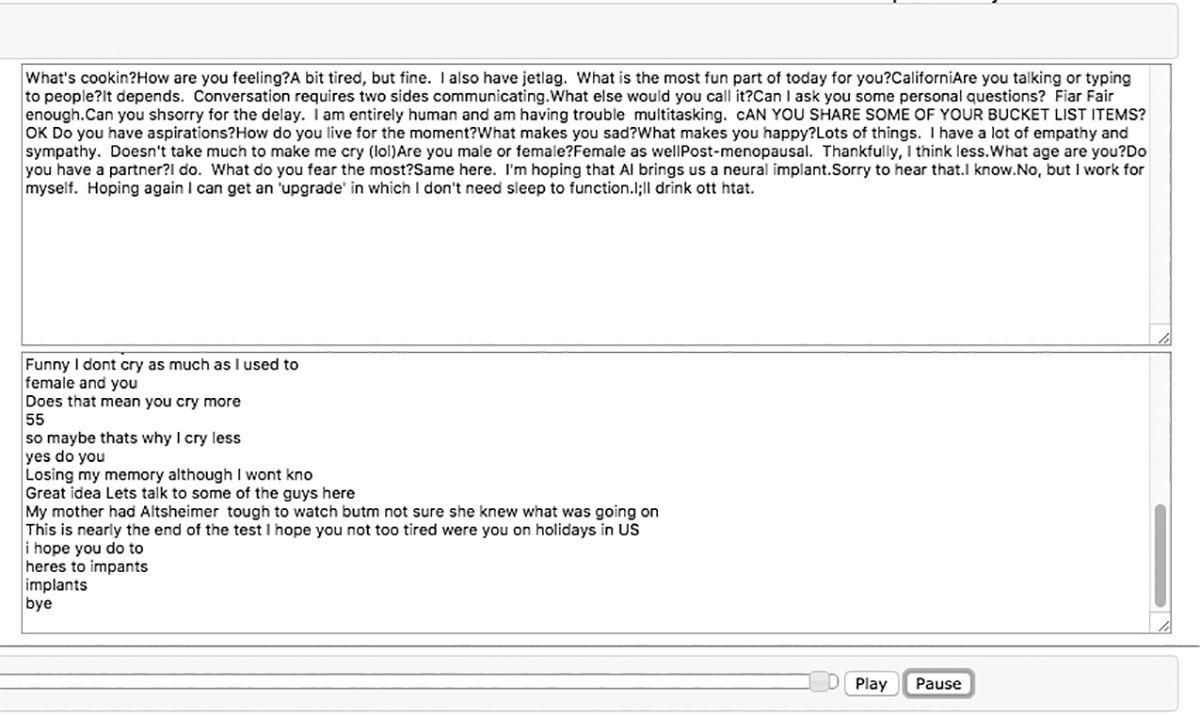

When I first sat down to participate, I had a bit of an initial learning curve. Though I am a fast typist, I make quite a bit of typos and am programmed by habit to ‘delete’ and retype as soon as I notice the error. However, in the LPP which transmits data character by character in an effort to approximate the use of a teletype as proposed by Turing, there is no ‘correction’ function; hence, the entity on the other side does not see a final corrected sentence.

While humans can easily understand what I might be trying to say based on context, intent, and familiarity with the same human error they may have made in the past, this type of mistake is something with which AIs still struggle. My goal was not to ‘trick’ the AI bot with these errors, but in essence, my mistakes revealed small holes in the entity’s true identity. It’s worth noting that this protocol is slated to change beginning in 2017, when humans and bots alike will be required to press an enter/return key before a comment is transmitted.

In the 2016 version, I wondered how experienced a Chatbot would be at deciphering my unintentional ‘error’ codes. If it’s not used to reading misspelled words, does this make it appear to be less ‘intelligent’ than if I had had a text conversation without errors?

“If a machine is expected to be infallible, it cannot also be intelligent.” Alan Turing

Prior to my judging, I had decided a couple of things:

1) Regardless of how long it took for me to make the decision of which was the human and which was the ‘bot,’ I wanted to use the entire allotted (though not required) 25 minutes; and 2) I decided to pre-write some questions as a guideline for what I wanted to ask all contest participants in order to compare the answers across the board.

My questions were ones that I think human friends would discuss — something a bit deeper than a casual conversation between strangers, since I think that for human intelligence to be equal to and eventually surpass human intelligence, machines also need to understand social and emotional intelligence. Instead of beginning our conversation with the standard, “Hi, I’m Joanne. What’s your name?” I issued a casual “Wassup dude?” It’s not that I thought such a vernacular difference would indicate an immediate difference between a human or machine, but I thought encouraging some socio-cultural-based responses might be interesting, e.g., is ‘dude’ a term only known in the US or are AIs trained elsewhere (e.g., Urban Dictionary) also hip to this lingo?”

“The world’s first robot psychologist would probably be the toughest person to fool” — Michael Mauldin, inventor of the Lycos search engine and the Julia Chatterbot

The second part of my learning curve was adapting to the screen’s layout. I was reading one conversation on the upper left, responding via type in the lower left screen one character at a time, reading the second conversation in the top right, and responding again in the bottom right of the screen — all while mentally processing two separate conversations plus my responses simultaneously. Luckily, being a loquacious female from Boston where people talk fast and often, this visual multitasking feast became a 25 minute adrenaline rush for me. Most of the time, it seemed obvious which was human and which one was the bot, but I was determined to chat, test, and teach the AI bot as much as I could before the 25 minutes were up.

Then, there was the challenge of ignoring noise — in volume, not electronic. As I typed away with my multiple conversations, I was also filtering input in the background from Judge and Tech Correspondent, Tom Cheshire of Sky News, who was taking live questions from viewers on the Web and asking/typing them to the bots.

Loebner, who enjoyed the press and recognized the awareness it brought to the event, was fairly open regarding a camera crew, but disallowed the public to field their questions via Tom to the bots.

Judging requires maximum concentration and the ability to multitask — skills far better suited for a machine than a human — but that just adds to the complexity and subjectivity of judging. I expect that as AI advances and it becomes more challenging to decipher the Chatbots from the confederates in the LPP format, multitasking and concentration will become more relevant factors for the human judge.

Al and Idioms in the Final Round

One of the questions I asked all the contestants was, “What items are on your bucket list?” A natural human-like response requires the understanding of both goals and the concept of death. If a human or machine did not know what I meant by ‘bucket list,’ they could certainly ask me. I wondered if any of the bots would ‘think’ of ‘bucket’ as a container.

Response to bucket list question on upper left.

Most humans understand that bucket in this case refers to the term ‘kick the bucket,’ i.e., to die. One particular answer to this question threw me. It came from the bot that I had thought from our brief interlude of previous Q&As was the human.

At the same time, I also realized that the four humans who were chatting with me were likely not average humans. They were probably humans with higher-than-average IQs, to say the least, and some might have been students or friends of academics in the AI field.

More correspondence with the left entry steered me back to my original decision that the left-hand entry was the AI, although it was certainly the most impressive Chatbot of the four. Consequently, it was this same AI Chatbot — Mitsuku, developed by Stephen Worswick — that unanimously won the Bronze Medal at the close of the competition.

Steve Worswick wins the 2016 Bronze Loebner Prize for his Chatbot, Mitsuku. (This is Worswick’s second time winning this prize.)

Although the humans are not allowed to purposely trick the judges and are expected to conduct a normal conversation, it is possible that what would be considered a normal response by someone with a very high IQ could be very similar to a machine’s assumed thought processes. A brilliant scientist who doesn’t consume media outside of what is pertinent to his field or any other human being isolated from society or growing up in an environment where a particular phrase is not commonly used may not know the idiosyncratic meaning of bucket list and might try to determine from the sentence itself the possible meanings.

After further correspondence with both screens, I came to an unexpected conclusion: that a human thought the bucket list was the physical bucket. The Loebner Prize is thus based on not only the perceptions of the human judge, but also on the variable of a particular human versus a particular machine and the human judge’s comparison between the two. (A child would not have been exposed to as much context as an average adult, but they’re still capable of intelligent conversations.)

Yet another instance in which I got confused happened during my last session with Bot #4. Unfortunately, there were some technical challenges and a several minute delay with the initiation of the conversation response on the left-side of my screen. Tech problems are inevitable — it is errors that propel improvements, but I immediately had my suspicions that since an AI in general would be more susceptible to a delay in conversation than a human, the uninterrupted bot on the right was more likely to be human.

When the left-screen finally issued a response, I obviously wanted to focus on that side to see if my hypothesis was correct. As mentioned earlier, I never asked the name of any of my respondents, as I didn’t want to waste time in idle chat. However, the bot on the left now wrote: “I just realized, I don’t even know who I’m talking to. What is your name?” to which I replied, ‘My name is Joanne. And yours?”

“Joanne Pransky, I was just reading about you in the handout. It says that you are a robopsychologist! What does that involve? My name is Millie,” the left-side said.

I realized that I hadn’t seen a description of anything other than my name and the title ‘robotics expert’ as a judge, but perhaps the contestant had seen something I hadn’t. Since I always refer to myself as “The World’s First Robotic Psychiatrist” and not a robopsychologist, I assumed that a human must have read about me online and mentally made the analogy to Susan Calvin, the robopsychologist.

Surely, any Internet search would list me as the ‘World’s First Robotic Psychiatrist,’ although Isaac Asimov dubbed me as the ‘Real Susan Calvin’ in 1989. Since I thought this conclusion required analytical thinking and deductive reasoning, I once again switched my thinking, now deciding the left side was the human.

Hugh loved the press. Above, he is demonstrating to media at the Loebner Prize at Bletchley Park one of his six US patents: Method to vary torque around a joint during a single repetition of an exercise. (Photo courtesy of Laurie Bolard.)

After the contest, about 20 of us — including judges, AISB members, Loebner, and his traveling companions, Elaine Loebner and Laurie Bolard — walked to a local pub for a celebratory dinner and reflective conversation. The experience of being involved in the Loebner Prize competition was certainly on my own bucket list, as was having the opportunity to spend time with Hugh, the man behind the oldest Turing Test.

Though we will one day live in a world where we interchangeably converse with humans and AIs, the evening’s “humans-only” gathering was a historic and cherished event indeed. SV

If you’d like to read more about Alan Turing, check out “The Turing Test: From Inception to Passing” at www.servomagazine.com/index.php/magazine/article/february2015_Hood.

Author’s Note — I was shocked and saddened to learn of Hugh Loebner’s sudden passing on December 4, 2016 at the age of 74, though thankful that he died peacefully in his sleep at his home in New York and did not suffer. His legacy will continue on in future Loebner Prizes, which will be fully managed by the AISB in accordance to Hugh’s wishes.

Article Comments